Carefully designed paragraphs are the key to well-structured and easy-to-read texts. If you feel like your manuscripts are hard to understand and lack a flow and logical structure, learning the art of paragraph writing might be just the solution you need.

How do you make paragraphs in your scientific texts? Do you proceed intuitively, as one researcher admitted to me recently? He reported to start a new paragraph simply when the current one gets “long enough”. But is this really a good criterion? If you have any doubts about how to best structure your scientific text in paragraphs, then this article is for you.

One idea per paragraph

The golden rule of writing great paragraphs is to discuss only one idea or topic per paragraph. A paragraph allows you to introduce, discuss, and conclude an idea in a “single package”, which makes the reader’s job as easy as it can get.

To test whether a paragraph really contains a single topic is simple: try to express the topic of your paragraph in one sentence. If it is not possible to find an overarching theme for all the details contained in your paragraph, then you should either split the paragraph (if it deals with several different points) or think about what you want to say with that paragraph in the first place (if it seems like the paragraph is not making any point at all).

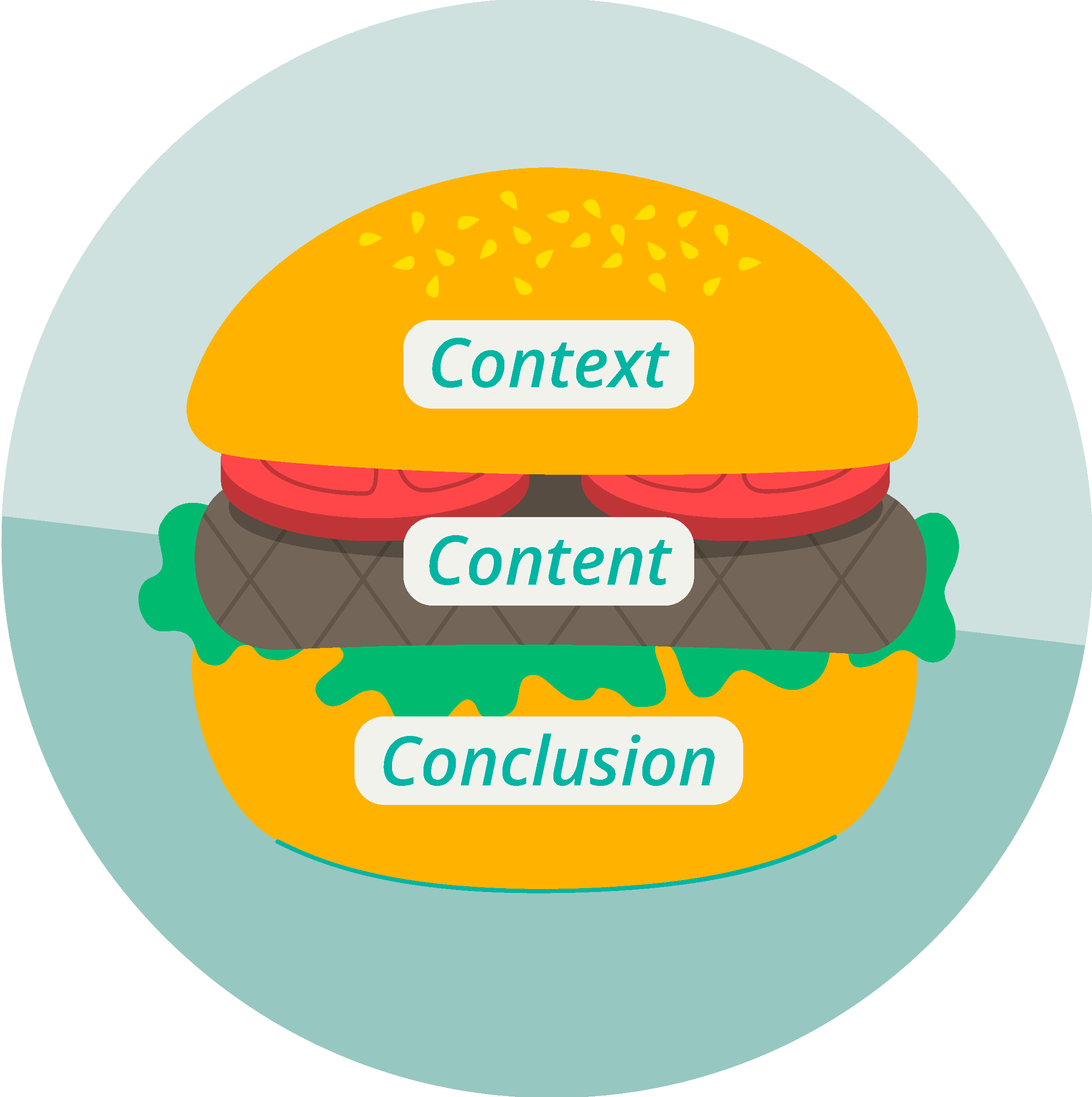

The hamburger structure of paragraphs:

Context-Content-Conclusion

This topic sentence, the sentence containing the main point or introducing the topic of the paragraph, makes for the perfect beginning of your paragraph. It gives the reader an idea of what the paragraph is going to be about — it provides context which enables the reader to easily follow the subsequent reasoning and understand the details even when they are complex. Moreover, the proper use of topic sentences allows the reader to gain an overview of the article content by just reading the first sentence of each paragraph. Check out how it works with this article and its topic sentences.

On the other hand, if you omit the topic sentence and start out with details, your reader will need to keep everything in their mind until you finally provide the key to tie all those details together. If the topic you write about is complex (and I bet your research project is complex), this approach typically leads to a cognitive overload of your reader. Maybe you have read paragraphs like those before: when the paragraph finally comes to the point, you need to read it again to really understand it. So don’t start with the details, start your paragraphs with the topic or main point and help your reader avoid the frustration!

As the topic sentence is the optimal beginning of your paragraph, a closing sentence providing a brief summary or conclusion is the best way to wrap-up the contents of your paragraph and create a smooth transition to the next paragraph. A closing sentence can be safely omitted in short paragraphs dealing with rather simple and straight-forward ideas, but it is an essential element when discussing more complex topics.

Let’s consider the following text as an example. As you read it, pay attention to the topic and closing sentences.

Creativity has been associated with mental illness for centuries. Biographical accounts of famous musicians, philosophers, scientists, writers, artists, and poets describe psychotic episodes and suicides [REF]. Psychological studies have shown that, on average, highly creative people have higher scores on measures of psychopathology than less creative people [REF]. Furthermore, relatives of schizophrenic or other psychotic patients have a higher incidence of creative achievement [REF].

However, the relationship between characteristics of ‘genius’ and symptoms of ‘madness’ is not straightforward. The majority of people who suffer from chronic mental illness experience a wide range of symptoms and deficits that interfere with the production of substantive work. Moreover, creativity is often defined as the ability to produce new ideas and adapt, improve, or create new functions for existing products [REF], skills that are impaired in most patients with schizophrenia. Indeed, the productive periods of most famous creative individuals occurred when their symptoms of mental illness were less severe [REF]. It therefore seems useful to examine whether creativity is associated with certain emotional, cognitive, or personality traits that may also predispose one to mental illness.

In the first paragraph of the example, the topic sentence expresses the main point of the paragraph: the long-standing association of creativity with mental illness. The subsequent sentences support this main point with examples and details and there is no need for a concluding sentence. On the other hand, the second paragraph deals with a more nuanced question of the precise link between creativity and mental illness. The paragraph body provides contrasting evidence, so a closing sentence is appropriate, even necessary, here: to conclude the dispute and provide a “take-home” message for the reader.

As we have just seen, the topic and closing sentence create a framework that holds the paragraph content together just as the top & bottom half of a bun hold together all the various toppings and ingredients of a hamburger. In the same way as the hamburger bun allows you to easily manipulate and eat the richly stuffed hamburger, the topic and closing sentences allow you to easily understand the paragraph and its connections to the preceding and following one, even when the text treats a complex issue.

Maybe you have heard about this paragraph structure as the Context-Content-Conclusion model. Accordingly, the first (topic) sentence creates the context for a better understanding of the content of the paragraph, while the last (closing) sentence provides a summary or a conclusion of the paragraph.

Exercises

Now you know the theory of how to structure your paragraphs for maximum comprehensibility. The next step is to try it out yourself, to transform this passive knowledge into active skill. Hence I prepared for you the following exercises:

- Consider the following paragraph from an Introduction section. Does it follow the hamburger structure? If not: what is the problem? Can you fix it?

Any search or foraging act represents a balance between exploration and exploitation: One the one hand, one must search or explore the environment in order to find and learn about desired resources; on the other hand, one must exploit those resources in order to accumulate gains. Consequently, striking a balance between exploration and exploitation is the key to successful foraging. But does aging impact the control of exploration-exploitation trade-offs?

- Pick a research article you have read recently. Read the topic sentences of all paragraphs: do they communicate the whole story of the paper? If not: which parts work well, and which don’t? Can you improve some of the topic sentences?

- Then choose one or two paragraphs from the Introduction or the Discussion section. Do they follow the hamburger structure? If not: what is the problem? Can you improve them by, for example, splitting them or adding/changing the topic or closing sentence?

- Do you have a paragraph that is not working, but you are not sure what is the problem and how could you improve it? Share it in the comments and ask your peers for help.

Do you want to get example solutions and further explanations about the exercises? Then sign up for our Newsletter and gain access to our exclusive writing resources!